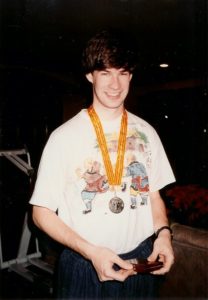

Portrait of Matthew Polly, writer and author of “American Shaolin”

©JUSTIN GUARIGLIA

WWW.EIGHTFISH.COM

Matthew Polly is the national bestselling author of American Shaolin, Tapped Out and Bruce Lee: A Life. A Princeton University graduate and Rhodes Scholar, he spent two years studying kung fu at the Shaolin Temple in Henan, China. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Esquire, Slate, Playboy, and The Nation. He is a fellow at Yale University and lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

Q1. Kung Fu, Chinese culture, and language were at the forefront of your life in your younger years. Could you tell us a bit about your background, and how your interest in kung fu shaped the person you are today?

I was one of those skinny, scrawny kids who got picked on by the bullies. When I was 12 years old, I watched Enter the Dragon for the first time. Bruce Lee leapt off the screen and into my imagination. Here was this skinny, scrawny guy who appeared invincible. I wanted to be just like Bruce Lee.

Q2. You took a break from Princeton to train at the Shaolin Temple. Did you see it as an escape, a challenge, or a calling at the time?

I was a religion, and East Asian studies major at Princeton. I told my parents I was taking time off from Princeton to research my senior thesis on the Shaolin Temple. The truth was I didn’t like who I was as a person. I wanted to be a better version of myself —more daring, more courageous, more self-confident. One of the great attractions of travel is that it allows us a chance to become someone new. And if we live in a different place long enough some of those changes stick after we come back home.

Q3. I read some of your stories; you were the first American accepted as a Shaolin disciple. Take us back in time. Did you feel any culture shock when you arrived, and how did you adjust to life there?

I lived and trained at the Shaolin Temple from 1992-1994. At the time, China, especially rural China, was still very poor. People would often go hungry. It was a shock to live with smart, talented people who had almost nothing. But the biggest adjustment for me was learning how to be a minority of one. I was the only white person in a 500 mile radius. The Chinese were very kind to me, but they always treated me as a foreigner, someone different. It can be exhausting always feeling different.

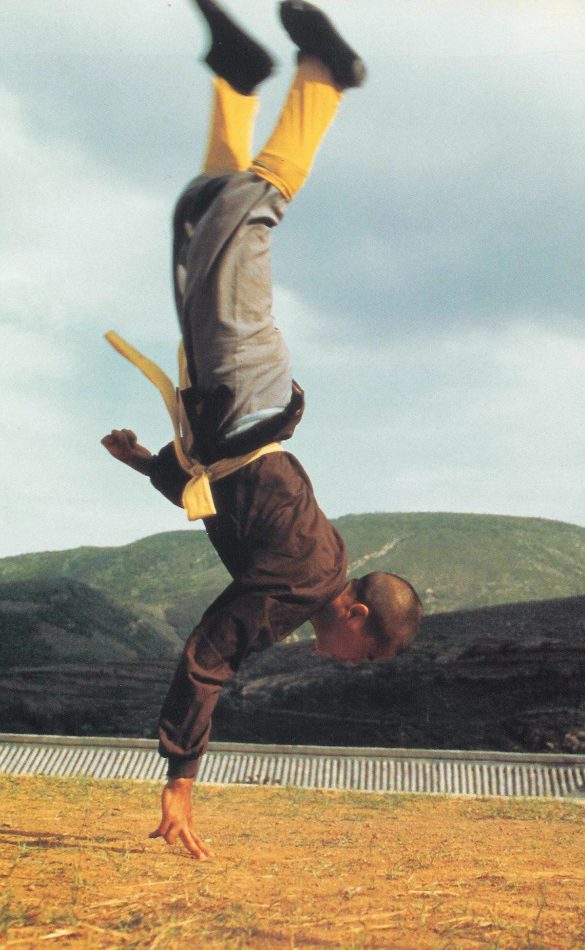

Q4. Shaolin always comes across as kind of mysterious, and movies and TV often portray Shaolin monks as having superhuman powers. Could you walk us through what a typical day was like for you at the Shaolin Temple?

When I was at the Shaolin Temple, there were about 10,000 Chinese kids studying kung fu. They came at an early age (8-10) and trained 6-8 hours a day for a decade. The top 50 or so of the 10,000 kids were invited to become Shaolin monks. They seemed superhuman because of all the training and because they were the best of the best. There wasn’t any TV, movies, internet, social media, or smart phones. All there was to do was kung fu. It is a brutal system, but it creates incredible athletes.

Q5. Media always associates martial arts, especially Chinese kung fu, with cultural identity, the fact is, it is a form of physical art with much deeper significance. Could you share your insights on what kung fu has taught you beyond its cultural significance?

I like to joke that kung fu is China’s way of tricking 13-year-old boys into meditating. On the surface, kung fu is about fighting (that’s why teenage boys are into it), but at its deepest level, kung fu is a form of moving meditation, a religious ritual. As martial arts practitioners get older, they begin to better appreciate this spiritual aspect.

Q6. One of the kung fu legends who has influenced you is Bruce Lee. You have written a story about him. What is one story about him that has had a profound impact on you?

Bruce Lee was an incredible martial artist, but what impressed me most about him is that he was the first Chinese actor to ever star in a Hollywood movie. It was 1972 and even Bruce’s closest friend in Hollywood said it was impossible because of the racism at the time. But he never gave up. He kept pushing. And he finally achieved his dream of becoming an international movie star.

Q7. What approach do you use when writing about martial arts to help western readers connect with Eastern culture and philosophy?

It is much harder to grasp concepts abstractly. It is much easier in terms of story or people. I like to write about the people I meet and describe our interactions, like a novelist, and let the differences in culture and philosophy flow from there. Sometimes it is necessary to stop and explain a foreign concept to the reader, but more often than not the stories themselves do the talking.

Q8. Could you share a unique experience from your travels, especially your time in China, something really stood out and still stays with you?

When I landed at Beijing airport I didn’t know where the Shaolin Temple was, except someplace in China. It took five days for me to ask various strangers before I finally narrowed it down. I was lost and that made it an adventure. I’ll never forget the thrill and the terror. But ever since GPS, the internet, and smartphones, I’ve never been lost. The world is an easier place to travel in, but something was lost when it became impossible to get lost.

Q9. Your message to our readers, especially especially those interested in martial arts?

The advice for anyone wanting to train in the martial arts is the same for anyone who wants to write…. Just do it. Pick a local martial arts school, sign up, and start training. If you don’t like it, pick another studio. Eventually you will find the right home, and, if you work hard enough, eventually you will get pretty good at it.

Photo credits: Matthew Polly (unless stated otherwise)

Leave a Reply