The province of Ifugao sits in the Cordillera mountain range of Northern Luzon in the Philippines, a region where time seems to move differently than in the congested streets of Manila I had left behind just a day earlier. As we climbed higher into the mountains, the air grew noticeably cooler and cleaner, carrying the sweet scent of pine and the earthy aroma of recent rain.

“First time in Ifugao?” asked the elderly man seated beside me, his weathered face creasing into a kind smile. He introduced himself as Mang Delfin, a native Ifugao who had spent decades as a tour guide before retiring to tend his family’s ancestral rice fields. When I nodded, his eyes lit up. “Then you’re about to see something that will stay with you forever.”

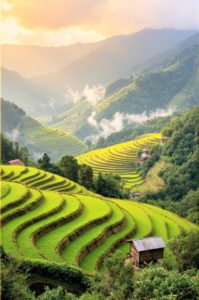

As we rounded a bend in the road, the landscape suddenly opened up before us, and I understood what he meant. Stretching as far as the eye could see were amphitheaters of perfectly sculpted terraces, following the natural contours of the mountains. Each terrace was a masterpiece of human ingenuity, carved into the mountainside and held in place by stone walls. The morning sun glinted off the water-filled paddies, turning them into mirrors that reflected the sky and created an otherworldly mosaic of blues and greens.

“The ancestors built these by hand,” Mang Delfin said, his voice filled with quiet pride. “No machinery, just human determination and knowledge passed down through generations.”

The Terraces during green season (Image: Lola Pinay Designs and Art).[/caption] Our vehicle stopped at a viewpoint, and I stepped out to fully absorb the panorama. The terraces of Batad, one of the five clusters that make up the UNESCO site, formed a perfect amphitheater below us. Fellow travelers clicked photos frantically, but I found myself putting my camera away, wanting instead to commit this view to memory without a lens between us.

After checking into a simple guesthouse in Batad village, I set out with Mang Delfin, who had graciously offered to be my guide for the day. The path down to the terraces was steep and muddy from recent rain, and I was grateful for the walking stick he had insisted I bring along.

“The Ifugao people have a deep connection to these terraces,” he explained as we descended. “They are not just agricultural fields—they represent our spiritual beliefs, social structures, and traditional knowledge systems. When a young Ifugao inherits a terrace from their parents, they inherit a responsibility that goes back 2,000 years.”We reached the first level of terraces, and Mang Delfin showed me how to walk along the narrow mud dikes that separated one paddy from another. I stepped carefully, aware that a single misstep could damage what had taken generations to build. Up close, I could see the complex irrigation system that channeled water from mountain springs down through each terrace, ensuring that even fields at the highest elevations received enough water.

“The system is sustainable,” Mang Delfin pointed out. “Water enters at the top terrace and flows down through each level. The mud and nutrients settle in each field before the water moves on to the next. Nothing is wasted.”

As we walked, we encountered farmers tending to their crops. Many were elderly, and I couldn’t help but wonder about the future of these terraces. Mang Delfin seemed to read my thoughts.

“Many young Ifugao leave for the cities now,” he said with a hint of sadness. “The work is hard, and modern life is tempting. But there is a revival happening. Some are returning, recognizing the value of our heritage.”

We stopped for lunch in a traditional Ifugao hut, or bale, with its distinctive pyramid-shaped thatched roof. The owner, a woman named Mariana, served us pinikpikan, a traditional chicken dish, and dinakdakan, a pork dish flavored with bile that was surprisingly delicious despite its intimidating description. The meal was accompanied by locally grown rice, which had a distinct nutty flavor unlike any rice I had tasted before.

“This is tinawon,” Mang Delfin explained. “Traditional Ifugao heirloom rice. It takes longer to grow than modern varieties, but the taste is worth it.”

After lunch, we hiked to Tappiya Falls, a two-hour journey that took us through more terraced fields and into the dense forest beyond. The waterfall was a powerful cascade dropping into a deep pool of turquoise water. Despite the cool mountain air, several local teenagers were swimming, and they laughed and waved for me to join them. The cold water was shocking but invigorating after the long hike.

As the sun began to set, we made our way back to the village. The changing light transformed the terraces once again, casting long shadows that emphasized their three-dimensional quality. We stopped at a small wooden structure that Mang Delfin identified as a native rice granary.

“This is where we store our harvested rice,” he said. “The design keeps out pests and maintains the right humidity. Our grandfathers built them to last generations.”

That evening, I was invited to witness a community gathering where elders performed traditional Ifugao chants and dances. The mumbaki, or native priest, explained through a translator that they were performing a ritual to thank the gods for a good harvest. The rhythmic sounds of gongs and the fluid movements of the dancers created an atmosphere that felt both ancient and timeless.

I spent the next few days exploring other terrace clusters in Ifugao—Mayoyao, Hungduan, Nagacadan, and Kiangan—each with its unique character but all sharing the same testament to human perseverance. In Kiangan, I visited its national shrine, a World War 2 museum, which also houses artifacts that tell the story of Ifugao culture beyond the terraces: intricately carved bulul (rice granary guardians), traditional textiles, weapons, and tools.

On my final evening, I sat on the balcony of my guesthouse, watching fireflies dance over the terraces as darkness fell. Mang Delfin joined me, bringing two cups of rice wine.

“What do you think of our home?” he asked.

I struggled to find words that could capture what I had experienced. “It’s more than just a beautiful place,” I finally said. “It feels like being inside a living history book, where the past isn’t dead but continues to shape the present.”

He nodded, seemingly pleased with my answer. “That is the essence of Ifugao. We don’t preserve our terraces and traditions like museum pieces. We live them.”

As I prepared to leave Ifugao the next morning, I reflected on what I had learned. These terraces were not just an engineering marvel but a testament to a harmonious relationship between humans and nature that had sustained for millennia. In a world rushing toward modernization, Ifugao offered a different perspective on progress—one that valued continuity, community responsibility, and environmental wisdom.

The journey back down the mountain was filled with a bittersweet mixture of gratitude for what I had experienced and sadness at leaving. As the terraces receded from view, I remembered what Mang Delfin had said on my first day: this was a place that would stay with me forever. Looking at the terraced mountains disappearing into the distance, I knew he was right.

Ifugao had offered me more than just spectacular views or a checkbox on a travel itinerary. It had shown me a different way of measuring time—not in hours or days, but in seasons and generations. It had demonstrated how a community’s identity could be inextricably linked to its landscape. And perhaps most importantly, it had reminded me that some of humanity’s greatest achievements aren’t towering skyscrapers or technological marvels, but the patient, persistent cultivation of harmony between people and the land they inhabit.

As my journey continued to other parts of the Philippines, I carried with me not just photographs and souvenirs, but a newfound appreciation for cultural landscapes like Ifugao—places where heritage isn’t something relegated to museums but is actively lived every day. In the careful tending of ancient terraces, in the preparation of traditional foods, in the performance of rituals that have endured for centuries, I had witnessed a profound expression of what it means to belong to a place and to honor those who came before.

The story of Ifugao continues to unfold, balancing preservation with adaptation, tradition with change. And while challenges remain for this remarkable cultural landscape, the enduring legacy of the terraces—and the resilient spirit of the Ifugao people—offers hope that this living heritage will continue to inspire travelers and sustain communities for generations to come.

Leave a Reply