Charles A. Ray is a retired U.S. diplomat and former ambassador to Cambodia and Zimbabwe. Before joining the Foreign Service, he served 20 years in the U.S. Army. Over his diplomatic career, he held key positions including Deputy Consul General in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Deputy Chief of Mission in Sierra Leone, Consul General in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for POW/Missing Personnel Affairs. He is a prolific author of more than 400 fiction and non-fiction books, with genres spanning leadership, history, diplomacy etc., and pens a weekly opinion column for Negros Weekly in Bacalod City, Philippines.

Charles A. Ray is a retired U.S. diplomat and former ambassador to Cambodia and Zimbabwe. Before joining the Foreign Service, he served 20 years in the U.S. Army. Over his diplomatic career, he held key positions including Deputy Consul General in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Deputy Chief of Mission in Sierra Leone, Consul General in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for POW/Missing Personnel Affairs. He is a prolific author of more than 400 fiction and non-fiction books, with genres spanning leadership, history, diplomacy etc., and pens a weekly opinion column for Negros Weekly in Bacalod City, Philippines.

Q. Before you became an ambassador, you were in the US Army, serving overseas in places like Vietnam and Germany. And later your Foreign Service career took you around the world again, from Cambodia to Zimbabwe. In your early days, did you ever picture yourself living this kind of life, or did it just happen as things came up?

It was actually a combination of both. My stepfather’s older sister had a collection of National Geographic magazines that she let me read when I was about five (my mother taught me to read when I was four). I was fascinated by places like The Great Wall and Stonehenge and determined to see them one day.

When I graduated from high school in 1962, living in Texas, where opportunities for African Americans were few, I decided to join the U.S. Army. I volunteered for Germany and, after training as a Morse Code radio operator, was sent to Augsburg, where I served for 18 months before being selected to attend Officer Candidate School in 1964 at Ft Sill, Oklahoma. I was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1965, and because I had not completed my B.S. degree, I decided to stay in for a while to finish my education.

During my time in the army, whenever an overseas assignment came up, I jumped on it. I went back to Germany —this time to Hanau— and after a year, I was brought back to the US., where I served as a training company executive officer at Ft Benning, Georgia, for six months, then applied for Special Forces Training at Ft Bragg, NC. During my time in the army, I served in Louisiana, New Jersey, Germany, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Georgia, Maryland, Vietnam, Kansas, Arizona, Korea, and California—a lot of countries and states. I visited many more.

In 1982, after serving 20 years, I wasn’t ready to settle down, so I took the Foreign Service exam and joined the Foreign Service in August 1982, concurrent with my retirement from the Army.

When Charles was ambassador to Zimbabwe, he visited one of the national parks and spent a day patrolling with the park rangers.

Q. In your foreign service years, you have lived in countries like Cambodia, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe. As an American, what is something that really surprised you while living across such diverse cultures?

Living in and visiting places as diverse as Sierra Leone, China, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand, Cambodia, and Zimbabwe, the thing that always surprises me is that, despite cultural and linguistic differences, people are at heart more alike than they are different.

For example, when I served in Cambodia, Hun Sen was the prime minister. A dictator, whose politics were diametrically opposite mine, we got along because we came from similar backgrounds and had similar life experiences – although mine were probably not as drastic as his, having been put on a list for execution by the Khmer Rouge because he married without getting the KR leadership’s permission.

As a diplomat, I used the similarities as a key to establishing a relationship that enabled me to discuss the differences without it becoming a rancorous argument. My philosophy, which served me well for 30 years, was, ‘disagree without being disagreeable.’

As the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for POW/Missing Personnel Affairs, Charles observed U.S. search-and-rescue exercises with Arizona first responders.

Q. In one of your articles, you wrote that the most critical parts of diplomacy are invisible, like the air we breathe, impossible to measure. What do you think are the strongest invisible forces in our human relationships, whether in diplomacy or everyday life?

Trust and credibility are diplomacy’s coins of the realm. Without them, you can know languages and history, but you will still struggle to influence people. You build trust by how you live your life and conduct yourself.

For example, if you tell people the truth even when you know it will upset them, over time, they might not like you, but they will respect you because they know they can trust what you say. I found that this worked with foreigners and Americans alike.

There was, for example, a congressional staffer I had to deal with, who didn’t like the State Department much and who was quite prickly. Because he was the clerk on a key committee that controlled the State Department’s budget, he was catered to by people from State. I refused to do this because I felt it was not only counterproductive to effective diplomacy but also wrong.

He and I were often at odds with each other, and I can’t say that we were anything resembling friends. But, at the end of my tour of duty, I visited him as a courtesy, and he said something that has stuck with me. “I disagree with most of what you say,” he said. “And a lot of what you do. But, I know that when you tell me something, I can trust it, and even though I can’t say I like you very much, I respect you.” That’s what every diplomat should strive for.

When Charles was Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for POW/Missing Personnel Affairs, he signed an agreement granting limited access to PLA archives to search for Korean War and World War II missing personnel. Here, Charles is being welcomed on a visit to the archives in Shanghai, as the first American official allowed to enter the unit.

Q. During your time in Cambodia, one of your big achievements as an ambassador was helping Cambodia get rid of its entire stock of portable ground-to-air missiles. When you look back on that now, what part still feels hard to believe?

Given the relationship of respect and trust I’d built with Hun Sen and members of the government, private sector, political opposition, and, probably most importantly, King Sihanouk, I didn’t find it hard to believe when they agreed to let us destroy their ground-to-air missiles. I explained why this was important, they accepted the explanation because it was true, and the deal was done.

Charles is with his driver Matthew Jong (on his right), two foreign tourists (to his driver’s right), and some locals (on his left), visiting one of Sierra Leone’s national parks that managed to stay open during most of the war.

Q. When you first arrived in a new country as a diplomat, what were some of the very first things you would do to feel the place and people?

The first thing I do, whether it’s a new country or a new organization, is get around and get to know people at all levels. I listen to them and ask them to educate me about their country or organization. Listening and asking questions intended to give you a better understanding of a place are always advisable. If you show sincere interest in people, they will reciprocate.

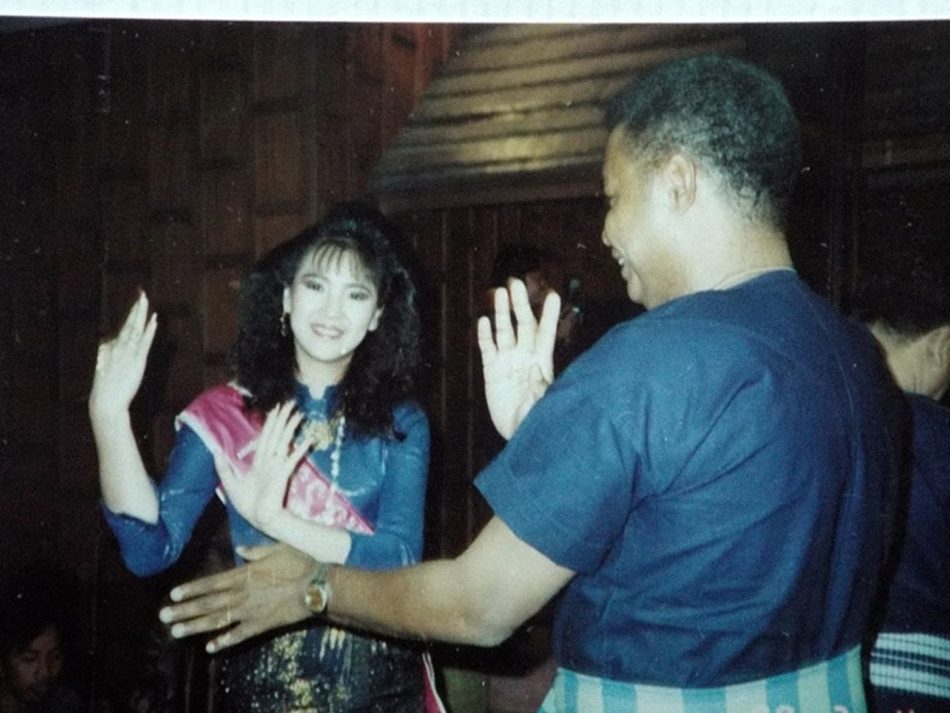

As U.S. Consul in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Charles participated in many local festivals. In this photo, he is performing a traditional dance during Song Khran.

Q. Back when you were a diplomat, most of your trips came with a mission. But now that you are retired, if you could travel just for the fun of it, you know, places that pique your curiosity, where would you go and why?

There are still a few places I haven’t seen that I’d love to visit. Antarctica and the Pyramids of Giza are just two examples. I’ve also not seen Hadrian’s Wall or Machu Picchu. I even have a few places in the U.S. I haven’t been to yet, like Yellowstone Park and Mount Rushmore. I want to visit places I’ve never been.

As ambassador to Zimbabwe, Charles supported U.S. educational aid programs. In this photo, he is pictured with Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai (on his right) and Public Diplomacy Officer Sharon Hudson-Dean (on his left) at a scholarship presentation.

Q. You are a prolific author and have written dozens of fiction and nonfiction books. How did your experiences in the military and diplomatic service inspire your writing, especially fiction that requires emotional nuance and authentic detail?

First, I have to set the record straight. To date, I’ve published over 400 books. In fairness, they are mostly pulp fiction, westerns, in fact, not that there’s anything wrong with pulp fiction. I like to entertain people with my fiction and inspire them with my nonfiction, but I also want to do both with each, if that makes sense.

My entire life inspires my writing, from growing up in a tiny Texas town that was rigidly segregated to 20 years in the Army, then 30 years as a diplomat. I observe people and situations, and use what I observe and my reactions to it in both fiction and nonfiction. For both, I also do tons of research. When I write westerns, for example, I try to have characters eat, dress, and speak the way they would have for the period of the story.

An example of authenticity: in my westerns, I don’t have my men putting belts on their trousers, because belt loops on trousers weren’t introduced until after 1900. When you see Western movies and TV shows that have men with belt loops, that’s a sign that the writers and directors haven’t done their homework. Emotional nuance in my writing is usually subtle. Instead of dwelling on it, I try to show character emotion through a gesture and let my reader figure it out.

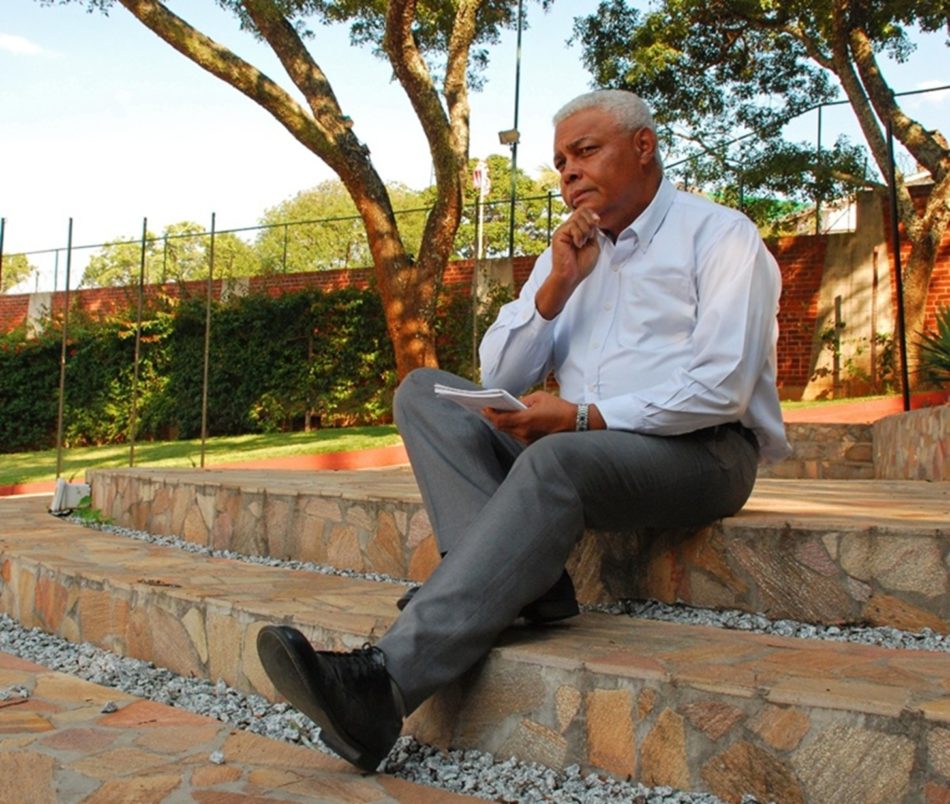

Charles sits under trees in Harare, Zimbabwe, notebook in hand, jotting impressions for one of his novels.

Q. Is there one country or posting that had a big impact on your writing voice?

Every place I’ve ever lived in or visited impacts my writing. I don’t think any one place has had more impact than the others.

Q. If you could give a message to diplomats in this polarized time, what would it be?

As an American diplomat, you swear an oath to the Constitution and promise to carry out the duties assigned to you to the best of your ability, even when you disagree with them. That’s extremely important in our current highly politicized environment, where loyalty to an individual and his policies seems to rank higher than loyalty to support and defend the Constitution.

I would imagine that many distasteful things are being asked of people now, some of which cross the line into illegality or unconstitutionality. In a case where your code of ethics is compromised, the only honorable thing to do is to resign.

My advice, though, is to make sure before taking such a step. If it’s clear-cut, no problem, but if it’s a matter of a difference of interpretation, study it carefully before deciding what to do. Our diplomatic service is being sidelined and marginalized, and there’s a need for people with integrity to try and hold on if we’re to preserve it.

All photographs credit: Charles A. Ray

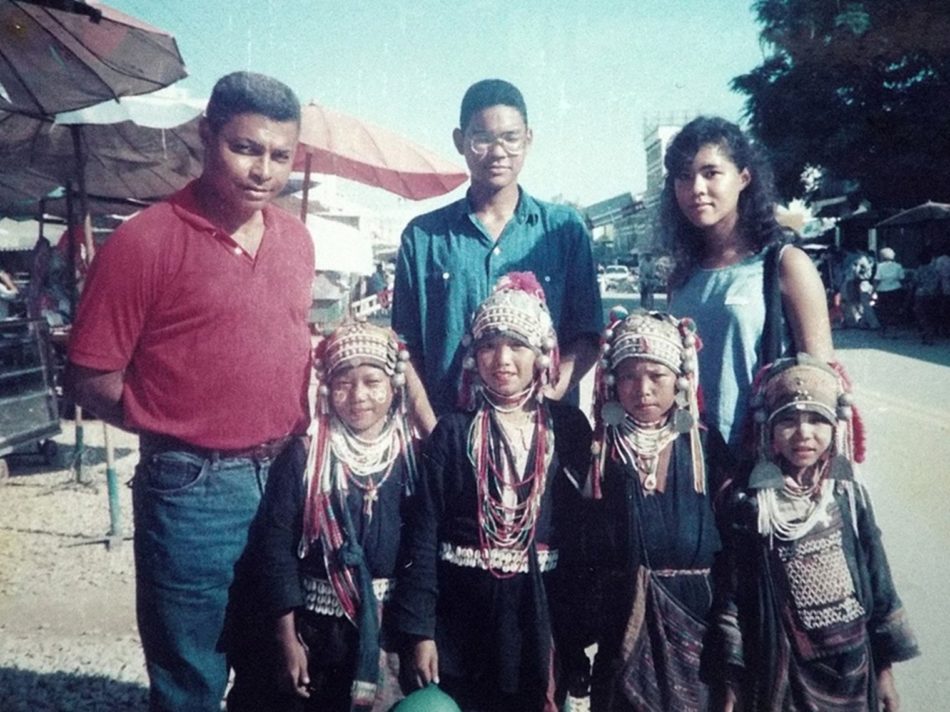

Charles, with his youngest son, David, and daughter, Denise, is pictured visiting a provincial town in northern Thailand during his time as consul in Chiang Mai.

Leave a Reply