Babak Tafreshi is an Iranian-born photographer, science communicator, and dark sky advocate. He is known for his work in astrophotography and nightscape photography, capturing stunning images of the night sky, including stars, galaxies, and celestial events. Tafreshi is the founder of The World at Night (TWAN), a global program that uses photography to raise awareness about light pollution and the importance of preserving natural nightscapes. He has also contributed to numerous publications, including National Geographic. Follow him on Instagram to see more of his work.

In this interview, Babak talks about his journey to becoming a night photographer, his love for the night sky, its importance to the environment, and how we can all help protect it.

Q. Could you share with us your childhood memories of growing up in Tehran and how your love for the night sky began?

My fascination with the night sky began at age 13 after viewing craters on the moon through my neighbor’s small telescope. I still remember that moment as if it were yesterday. I was hooked. Following this, I visited a planetarium and viewed the photo, “Earthrise.” My interest in astrophotography was ignited.

Iran has amazingly diverse landscapes and culture. As a teenager in the 1990s, my photography goal was to capture scenes of earth and sky in one frame. Pursuit of places where I could use my telescope and camera became my great passion.

It made me a traveler from an early age. My friends and I pursued celestial events such as eclipses and meteor showers, often using telescopes and basic camera equipment to create images on film. We often traveled as a group to remote villages and archeological sites that were far from the light polluted skies of Tehran. Chasing night skies in Iran became a fundamental part of my love of nature and exploration.

Q. What camera gear and equipment do you use for night sky photography, and what is your approach to post-processing?

I use a variety of gear based on the project and my clients. I am not really focused on one single brand of camera. Currently, I am using Nikon D850, Sony A7S, Canon Ra made for astrophotography, as well as Fuji GFX 100mp medium format.

I often use a variety of fast lenses from the Sigma Art series. These lenses have prime, fixed focal lengths and are among the fastest available on the market, allowing me to collect enough light in the shortest exposure time.

High on the Chajnantor Plateau, some 5000 metres above sea level it can get extremely cold at the site of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Babak Tafreshi, one of ESO’s Photo Ambassadors and part of the ESO Ultra HD Expedition team is shown here capturing the cool cosmos. The Milky Way can be seen to arc overhead.

Q. What was the most challenging night sky scene you ever captured, and what made it so rewarding?

There are many challenges in astrophotography when you deal with such a low-light environment. From a technical perspective, it is challenging for sure. But if you want to include the 4 elements that makes an image impactful: art, technique, moment, and story, having a moment becomes a challenge because some of the moments in astrophotography are not predictable, and some may take years to happen in the night sky, such as a great comet, a supernova in the galaxy or an atmospheric phenomenon.

To me, the most challenging night sky scene that I have captured has been the animals at nighttime, which includes my current project with National Geographic Society called “Life at Night Atlas.”

Reaching for stars. The bright central bulge of the Milky Way in the constellations Scorpius and Sagittarius appears in the dark and transparent sky of Cerro Paranal Observatory, Atacama Desert, Chile.

Q. You were an astronomy teacher back in Tehran. How did you use your skills as a science communicator to open the eyes of your students to the beauty of the night sky?

I started my career as a photographer and science journalist. I used the combination of my skills and experience to bring out the visual story that not only captured the attention of the audience, but also had some educational power. In framing a photograph, it’s crucial to include your intention, making the image impactful and a powerful tool for astronomy education.

An equirectangular panorama view from the Chilean Atacama Desert, showing the Milky Way shining brightly overhead.

Q. What’s one of the most memorable night skies you have ever seen, and your thoughts and reflections when you find yourself alone beneath the dark expanse?

The Atacama Desert in Chile is one of the most popular stargazing destinations. To me, its striking dark skies, dry weather, and atmospheric stability, which provide a remarkably transparent view of the deep sky, make it the most memorable.

I also have vivid memories of high-altitude treks in Nepal, especially towards the Everest base camp in 2009.

Time-exposure image of night sky has captured star trails (caused by the rotation of the sky) over Kilimanjaro in a moonlight night of Amboseli National Park, southern Kenya. The main peak of Kilimanjaro is Kibo that reaches 5,895 m (19,341 ft). The smaller peak is Mawenzi at 5,149 m (16,893 ft) and meaning the moon in Swahili.

Q. While there’s a global effort to combat the greenhouse effect, there seems to be little concern for the preservation of the night sky. What, in your opinion, has caused this lack of awareness, and how do you propose raising awareness?

Many people have never heard of light pollution. 99% of Europe and the United States live under light polluted skies; this is something that has happened over the past 100 years.

55% on Earth now live in urban areas where skies are dominated by sky glow. More than 80% of people have lost a connection to truly dark skies, as many places on Earth can no longer see stars in the night sky at all.

Light pollution has a major global impact not only for astronomers, but on nature and life on this planet. One of the most important things we should highlight is the effects this has on wildlife.

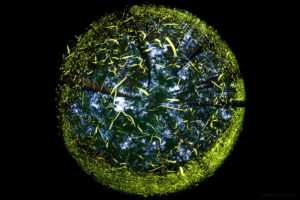

A long-expposure fisheye image of Sparkling Synchronous Fireflies under a forest canopy in the Great Smoky. They blink in sync, only when there is enough darkness and when there are lots of other lightning bugs nearby.

Migratory birds that navigate their long paths use magnetic fields, stars, and landmarks, which they remember generation to generation. New landmarks (bright light pointed to the sky) have been introduced to them and they are attracted to these lights. It completely disrupts their navigation system and brings them to the cities, where they get lost, collide with buildings, or die of exhaustion because they cannot find their environment or a place to rest. These facts are completely hidden to the public.

Light pollution affects insects, night-time pollinators (a major part of our food chain) and the human body by changing our sleep cycles. We need to make a culture change to not make everything “daytime bright.”

Removing excessive artificial light from our environment is one of the simplest things we can do. Culturally, we tend to associate brightness with safety, as in brighter is safer. We need to change the way we think about light pollution. Brighter is not safer, we must use light where it is needed, and in the warm part of the spectrum. We had no idea that light was affecting people and wildlife, but now we have come to that understanding.

Joining the International Dark Sky Association is the first important step toward addressing light pollution.

This impressive panoramic image depicts the Chajnantor Plateau — home of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA)

Q. In your opinion, how is the night sky perceived in terms of its cultural, spiritual, and personal significance in different regions and societies?

The sky is not the limit … Last night under the starry sky of White Mountains, California, 10,000 ft high.

The night sky was once a fundamental element in the lives of Indigenous peoples and cultures around the world. They used it for spirituality, and practical purposes such as a compass, map, and calendar.

Due to the expansion of light pollution in most parts of the world, a truly dark night sky has become a forgotten part of nature. The Milky Way is no longer visible to a substantial portion of humanity.

Being out under truly dark skies is a connection to earth and sky, your life and universe at the same time. This connection is exceptionally powerful and cannot be replicated in any other ways.

The natural beauty of the night sky is an important part of our humanity, which I believe is an essential element for life. The night sky is my second home and each time I stare up at a starry sky, I feel at one with nature and a strong connection to the past and the future at the same time.

Telephoto image of bright planet Jupiter, dust clouds in the Milky Way, bright star Antares in Scorpius, and Rho Ophuichi Nebula.

Q. The International Astronomical Union has named minor planet 276163 after you. What tremendous honor. How does this recognition make you feel?

I was greatly honored and incredibly surprised that Stefan Kurti, an amateur astronomer from Slovakia, discovered this minor planet and proposed to name it after me. It is a 2-kilometer-wide object and located in the main asteroid belt, not dangerous or near-Earth. I hope to photograph it with my telescope.

ESO’s Fulldome Expedition team arrives at the observatory in Paranal, where they are greeted in the languages of ESO’s Member States. Behind them, the array of telescopes stands proud on the mountaintop.

Q. Finally, your message to our readers and how they can get involved in The World at Night program (TWAN) and learn more about your book The World at Night?

TWAN is a volunteer initiative composed of the best night sky photographers from around the world. We all share a common passion for sharing the wonder of the night sky, both as a uniter of humanity and to generate public interest in preserving dark skies for generations to come. We rely on contributions from our photographers, coordinators, and individual supporters.

Throughout the years, my TWAN colleagues and I have spent thousands of nights recording scenes in some of the most remote corners of the world, many places most people will never get to visit.

I created “The World at Night” book of photographs featuring inspiring and educational stories of celestial events over famous landmarks and UNESCO world heritage sites to highlight the astronomical diversities of the night sky. I want these images to open doors to the beauty of science and introduce the night sky as a connection to nature, art, and culture.

You can get involved with TWAN by submitting photos and videos from their part of the world. Original ideas and images with unique stories are welcome. You can submit your work here.

All photographs credit: Babak Tafreshi:

World-renowed nightscape photographer and inaugural NOIRLab Photo Ambassador Babak Tareshi.

Was invited to the presentation at MIT Cambridge MA. Have to say I was totally clueless to what I would be seeing and who would be speaking, but found your presentation was to be totally amazing and eye opening. The information on light pollution helped me understand the impact on how our health is affected and how it is also a major danger to wildlife. Thank you so much!